Monetary Mysteries – Debt Sustainability or Inflation Control?

Since the early 1990s, Japan's potential GDP growth has collapsed while its debt has ballooned. It's no coincidence that Japan has become the world's monetary policy outlier!

Taking a step back often sheds new light on many matters, and monetary policy is no exception. The further I zoom out, the clearer it becomes that at least a few central banks have prioritized debt sustainability as their primary objective rather than inflation, contrary to what their official statements might claim. Japan serves as a prime example of this.

30 Years Ago

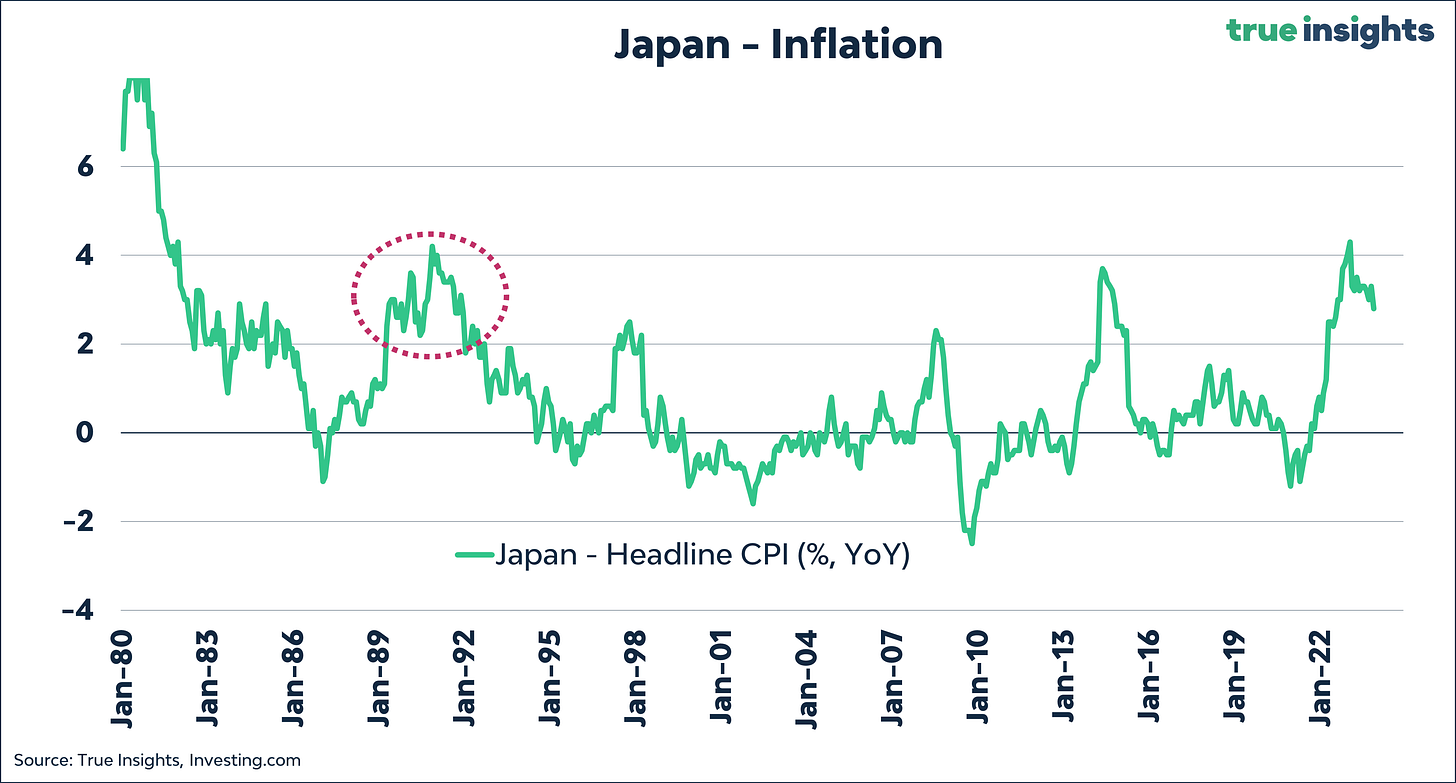

The graph below shows headline inflation in Japan since 1980. Since 1994, inflation has generally hovered close to 0, with a few notable exceptions swinging higher and lower. It’s widely recognized that Japan has an inflation issue, at least according to central bankers. One might wonder about the actual utility of deliberately eroding purchasing power. I’m pretty convinced that even with 0% inflation, businesses still aim for profit, and consumers will continue to buy. Yet, whether central banks should pursue inflation at all is beyond this post.

We have to go back more than 30 years, to the late ’80s and early ’90s, to find a period when inflation exceeded 2% for a longer duration than it does today. Back then, the Japanese economy was still ‘young and dynamic – or so let’s assume – and the then Bank of Japan Governor Yasushi Mieno believed that some ‘good old-fashioned’ tightening would keep inflation anchored. To put that in numbers, the Bank of Japan’s policy rate peaked at an impressive 6% in the early ’90s, with the 10-year rate topping this level. In contrast, today’s policy rate sits at -0.1%, and the 10-year rate is a mere 0.70 percent. The latter is the direct result of some form of excessive monetary policy we like to call ‘yield curve control.’ Japanese yield curve control has been active since September 2016, thus for about 7.5 years. For the central bank purists among us, it’s worth noting that the United States implemented yield curve control between 1942 and 1951. Yet, it does not require much imagination to conclude that the reason for that yield curve control was very different from the yield curve control deployed by the Bank of Japan today.

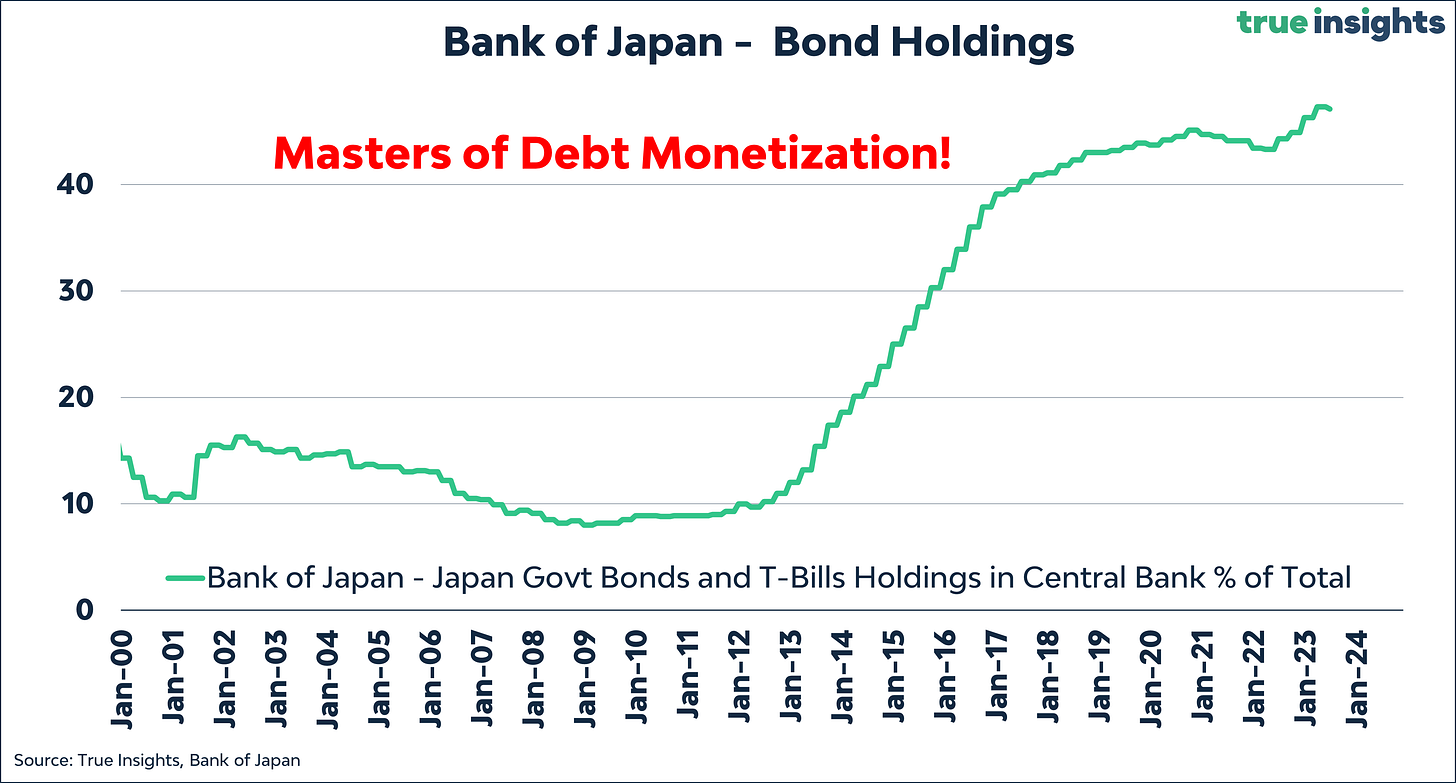

Meanwhile, the Bank of Japan now proudly holds nearly 50% of all outstanding Japanese debt. My Bloomberg terminal only goes back to 1999, but I can say with some confidence that this was not the case in the early ’90s.

Elephant in the Room

There’s one reason understandable reason why yields should be (somewhat) lower than 30 years ago. Japan isn’t growing. Potential growth is estimated between 0 and 0.5%, but I suspect it’s closer to the former than the latter. In the early ’90s, economists believed potential GDP growth was above 2.0%, which proved (very) incorrect. Nevertheless, as a central banker, you must make do with what you have.

But the real ‘elephant in the room,’ of course, is debt. In the early ’90s, Japan’s debt-to-GDP ratio was a tidy 62% of GDP. With a little effort, Japan could have easily joined the Eurozone back then, nearly complying with the Maastricht Treaty. One may only wonder why nobody talks about those criteria anymore. To be clear, Italy was already above a 100% debt-to-GDP ratio then. Yet, Japan’s debt now stands at 253% of GDP. While it’s often argued that part of Japan’s debt resonates within local governments and may be canceled out, a look at China, with their Local Government Financing Vehicles, suggests this would significantly impact economic activity.

Debt Sustainability

In summary, it’s crystal clear to me that central banks, whether by choice or not, are increasingly becoming the lenders of last resort for governments that perpetually overspend, regardless of the economy’s state. The Bank of Japan vividly illustrates the ‘solution’ here: structurally low or even negative interest rates. Good luck with that!

This post is based on one of my columns for Investment Officer.

Thanks for reading,

Jeroen

Until I read this article, I assumed that the debt the U.S. government has, is quite unsustainable. Don't ask me why I thought that, but the amount of debt is so enormous, that paying rent on that debt seems an undoable task in the long run. But as Japan seems to be able to do it, I guess the U.S. government will be able to do it as well. Just keep the interest rate in check and you're just fine. Or isn't that the gist of this article?