The Failure of First Republic: A Systemic Crisis in the Making?

An evidence-based analysis of the severity of the current US banking crisis

There continues to be much ‘guessing’ if the current US banking ‘crisis’ is systemic. But as we mentioned back in March: ‘During times of elevated uncertainty – it’s virtually impossible to have any conviction on whether First Republic Bank will make it – it’s crucial to put things into the ‘right’ perspective. ‘

By now, we know First Republic Bank did not survive, making the question of whether we are dealing with a systemic crisis even more relevant. Hence, we update our crisis assessment of the US banking sector using the leading database on bank failures of Laeven and Valencia (2012, 2018, 2020), which goes back to 1970.

Laeven and Valencia define a banking crisis as systemic when two conditions are met:

Significant signs of financial distress in the banking system (as indicated by substantial bank runs, losses in the banking system, and/or bank liquidations.)

Significant banking policy intervention measures in response to significant losses in the banking system.

Significant signs of financial stress – ‘V’

We believe this condition is met, albeit concentrated, at least for now, within regional banks. While FDIC counts only three failures this year – it does not count Silvergate ‘Bank’ as a bank failure – these are the 2nd, 3rd, and 4th largest in history. According to the FDIC, the total assets involved equal USD 549 billion. This compares to USD 374 billion related to the 25 bank failures in 2008, the start of the Great Financial Crisis. These numbers are not corrected for inflation, but it’s pretty clear that the ‘size’ of the failures is significant.

Next, deposits are fleeing both large and small banks on an unprecedented scale. Since deposits are at the heart of every bank run and many bank failures, this should at least cause some stress among policymakers.

In addition, the total market cap of US regional banks has declined by a whopping 80% from its peak in early 2022 and by 70% since cracks in Silicon Valley Bank started to emerge.

Yet, for the entire US banking sector, stress remains subdued. For example, the market cap is down nearly 30%, and bond spread levels are elevated but not extreme.

Could banking stress spike from here?

A recent paper by Seru and others (2023) estimates that the US banking system’s market value of assets is USD 2.2 trillion below the reported book value of assets. In addition, the authors conclude that if 50% of uninsured deposits (totaling USD 9 trillion) would withdraw,

190 banks with assets of USD 300 billion are at risk of impairment, ‘meaning that the mark-to-market value of their remaining assets after these withdrawals will be insufficient to repay all insured deposits.’ This is without taking into account contagion risks.

Obviously, the share of available-for-sale securities determines to what extent market-to-market valuations apply, and the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program aims to reduce the strain of paper losses. In addition, a 50% uninsured deposit flight is a heavy assumption. Yet, the analysis provides valuable information on the banking sensitivity to higher interest rates and deposit risk and suggests that further damage should not be ruled out. It also makes it clear that US regulators should consider (temporarily) guaranteeing all regional bank deposits.

Significant banking policy intervention measures – ‘X’

Laeven and Valencia (2012) ‘consider policy interventions in the banking sector to be significant if at least three out of the following six measures have been used:’

extensive liquidity support (5 percent of deposits and liabilities to nonresidents)

bank restructuring gross costs (at least 3 percent of GDP)

significant bank nationalizations

significant guarantees put in place

significant asset purchases (at least 5 percent of GDP)

deposit freezes and/or bank holidays.

1. Extensive liquidity support

Residential deposits are guaranteed or protected during almost every banking crisis. Without this, the fractional banking system would lose all credibility and implode. Therefore focus should be on liquidity provided to institutions directly by the central bank and government.

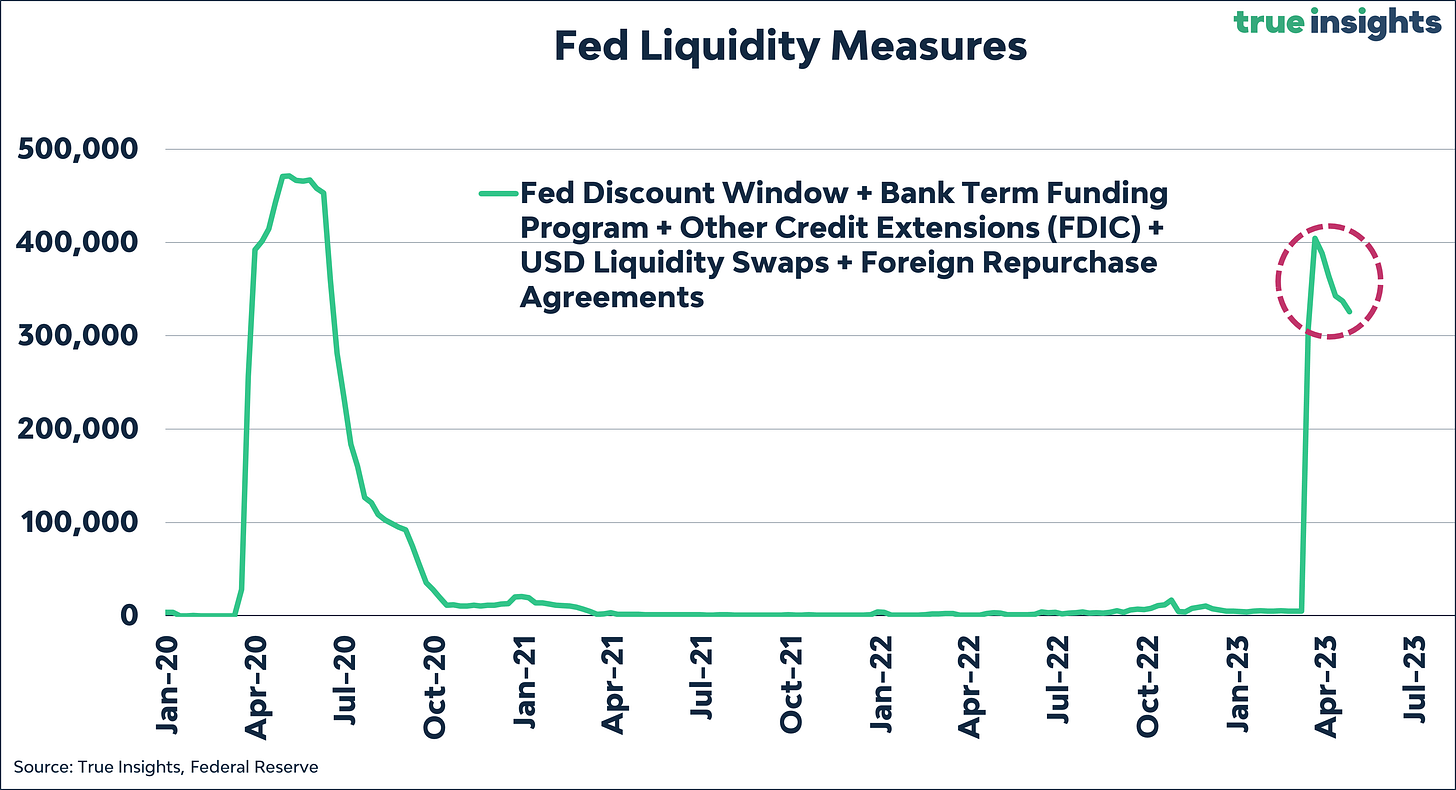

The chart above shows the cumulative (emergency) Federal Reserve Liquidity Measures, including the Discount Window, the extended currency swap lines (announced on March 19), and the new Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP). At its height, just after Silicon Valley Bank fell, these programs totaled USD 404 billion, representing 2.2% of total US commercial bank deposits. Not enough to match the condition of Laeven and Valencia.

However, these measures do not take into account the advances disbursed by the Federal Home Loan Bank System. The FHLB system functions as a lender-of-last-resort next to the Federal Reserve. It was launched after the Great Depression to support homeownership. But in more recent times, it tends to give early warning signs of rising banking stress. For example, in the second half of 2007, FHLB advances spiked by almost USD 230 billion, while nothing happened at the Fed’s Discount Window. But since banks commonly tap FHLB advances, linking increases to rising banking stress is less straightforward.

Yet, if we take the last two quarters’ expansion and label it stress-related, banks required roughly USD 380 billion in additional ‘liquidity.’ Adding this to the USD 404 billion in Fed measures represents total liquidity support of 4.6% of commercial bank deposits. That’s pretty close to the 5% required by Laeven and Valencia.

2. bank restructuring gross costs (at least 3 percent of GDP)

There has been no bank restructuring, with US national and regional banks swooping up the failed banks’ deposits. But even if the USD 36 billion FDIC losses (Silicon Valley Bank 20, First Republic 13, and Signature Bank 3) were loosely defined as costs to restructure the US banking sector, this would represent less than 0.15% of US (nominal) GDP.

3. Significant bank nationalizations

Bank nationalizations were crucial to the ‘solution’ during the Great Financial Crisis. The current environment includes no nationalizations until now.

4. Significant guarantees put in place

This has been the case in Switzerland but not in the US. First, while a significant range of eligible securities may be deposited at the Fed Bank Term Lending Program at par value – theoretically omitting the issue of paper losses – more exotic instruments on the banks’ trading books have not been included. Second, with national and regional banks taking over failing competitors’ deposits, the current dynamic resembles a game of ‘Whac-A-Mole.’ No structural, over-arching solution has been put into place. One example of this would be to guarantee all regional bank deposits.

5. Significant asset purchases (at least 5 percent of GDP)

Laeven and Valencia refer to asset purchases from financial institutions implemented through either the Treasury or the central bank. With several central banks trying to reduce their balance sheets, including quantitative tightening – this condition of significant policy intervention has not been met.

Even though the Federal Reserve’s balance sheet spiked by nearly USD 400 billion in the aftermath of the Silicon Valley Bank collapse, this was almost entirely explained by lending at the Fed’s Discount Window, the Bank Term Funding Program, and FDIC loans to make depositors whole. Recent policy intervention by the Fed should not be considered Quantitative Easing but does qualify as liquidity.

6. Deposit freezes and/or bank holidays.

As Laeven and Valencia point out, deposit freezes, while rare, are most frequently used by emerging economies.

Not ticking the boxes

Based on the definition used by Laeven and Valencia in their Systemic banking crisis database, we have not seen ‘significant banking policy intervention.’ None of the six criteria for significant policy intervention as defined by Laeven and Valencia have been met.

Obviously, the caveat here may be that the banking crisis will grow systemic BECAUSE policy intervention has been relatively muted compared to previous crises. With the US banking intervention resembling a game of ‘Whac-A-Mole,’ investors should not underestimate this possibility.

Sources:

Systemic banking crises database: An update ML Laeven, MF Valencia, IMF Working Paper, 2012.

Systemic banking crises revisited ML Laeven, MF Valencia, Ebook, 2018.

Systemic banking crises database II L Laeven, F Valencia – IMF Economic Review, 2020

Jiang, Erica Xuewei and Matvos, Gregor and Piskorski, Tomasz and Seru, Amit, Monetary Tightening and US Bank Fragility in 2023: Mark-to-Market Losses and Uninsured Depositor Runs? (March 13, 2023). Available at SSRN: https://ssrn.com/abstract=4387676 or http://dx.doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4387676