The latest IMF study on Inflation calls for even more rate hikes!

Based on an analysis of 100 inflation shocks from the past, the risks of premature celebrations are high!

The IMF recently published an exceptionally relevant and timely study, analyzing ‘100 inflation shock episodes in 56 countries since the 1970s.’ The results from this study confirm that, although the decline in US inflation after the Covid shock is faster than average, the risk of ‘premature celebrations’ is significantly high. This is especially the case for the Eurozone.

Fact 1: Inflation is persistent

The first fact concluded by the IMF is – unsurprisingly – that inflation lingers following shocks. The IMF calculated how long it took for inflation to drop to within one percentage point of the pre-shock inflation level for the 100 shocks it researched. And it takes quite a while. As the study concludes: ‘The results, shown in Figure 7, caution against anticipating speedy disinflation. Only in under 60 percent of episodes in the full sample (64 out of 111) was inflation resolved within 5 years after a shock. Even then, disinflation took on average over 3 years.’

Comparing today (I)

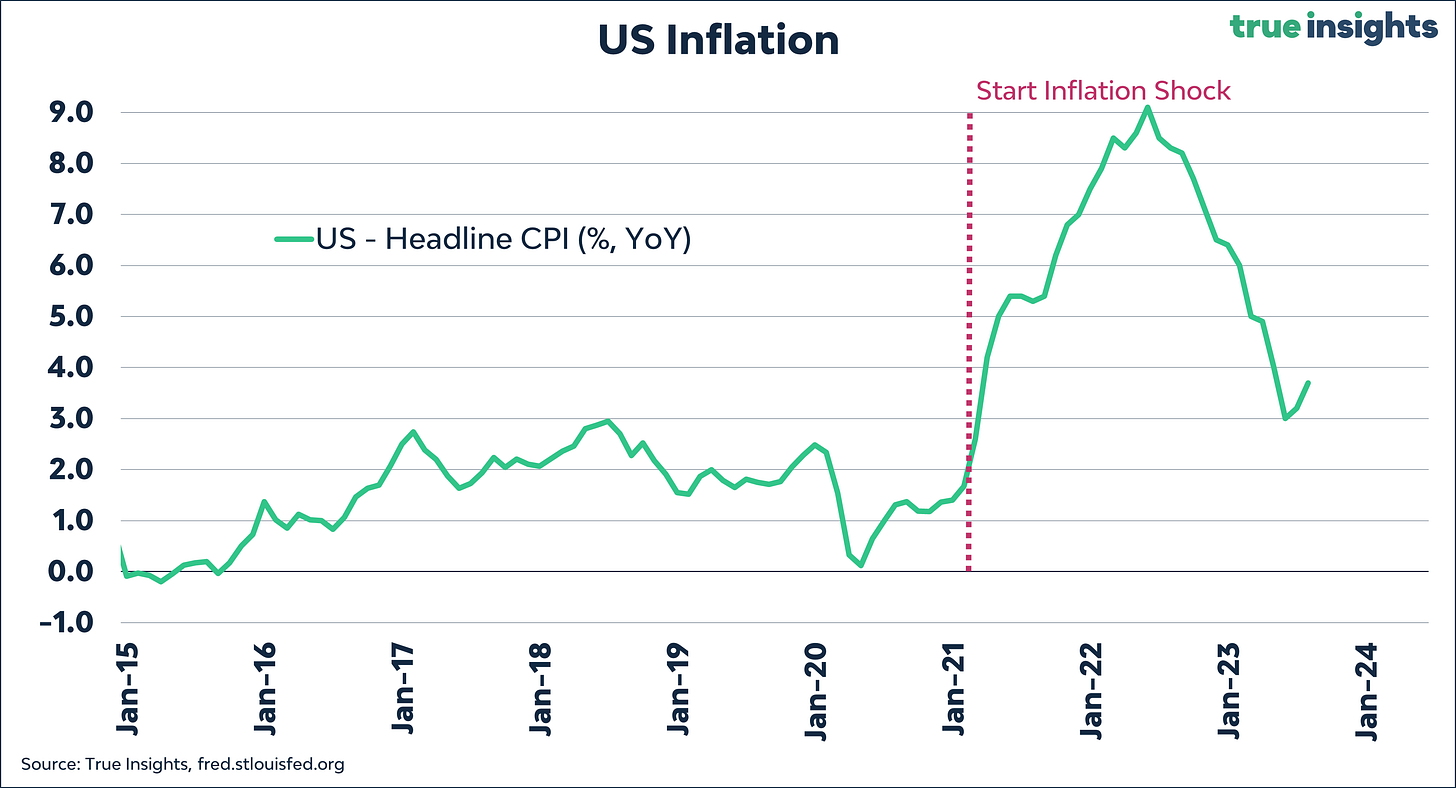

How does this compare to the most recent inflation shock? The chart below shows US headline inflation from 2015. The onset of the shock is – in line with the IMF’s methodology – set at the beginning of 2021. In June of this year, the inflation rate dipped to 3.0%, bringing it within a percentage point of the pre-Covid inflation level (2.3%). In other words, the US inflation shock disappeared faster than average.

We can’t yet say the same for the Eurozone. Similarly to the US, early 2021 marks the beginning of the inflation shock. However, more than 2.5 years later, the headline inflation still sits at 5.2%, far from the pre-Covid level of 1.4%. From this perspective, the ECB should adopt a more hawkish policy than the Federal Reserve, which likely explains why the ECB chose to raise rates once more, albeit with a disturbing and conflicting message attached.

Fact 2: Most unresolved inflation episodes involved ‘premature celebrations’

However, the real issue is the IMF’s second finding that victories over inflation are celebrated too quickly. After base effects have sharply pushed headline inflation downward, the underlying inflation-driving factors prove to be more stubborn than anticipated.

The following chart illustrates the most notorious example of ‘premature celebrations.’ After US headline inflation dropped from 12% to 5% in the mid-70s, the threat of inflation seemed to have passed. The Federal Reserve lowered the interest rate from a peak of 13% in 1974 to 4.75% at the beginning of 1976. However, this proved a grave mistake, as from 1977, headline inflation increased for three consecutive years, peaking at 14.8%.

Comparing today (II)

Below, US inflation is presented for various scenarios of headline CPI. The short-term impact of oil prices will cause problems. The price of Crude oil has risen almost 11% since the start of September, which roughly equates to an additional 0.7% CPI increase in September. This exceeds the scenarios depicted below, and the chance of inflation spiking back above 4% is becoming increasingly likely.

Until June/July, base effects linked to oil prices exerted significant downward pressure on headline inflation. However, with a recent oil price surge of 30%, this is no longer the case, as is shown in the chart below. If the oil price stabilizes at the current USD 92 (blue line), the year-on-year oil price changes will shoot up. Obviously, this effect will be exacerbated if the oil price continues to rise and reaches USD 120 by next June (green line). Only if the price starts to drop consistently from here, in this example, settling at USD 65 by June (purple line), the inflationary pressures from the oil price will not increase further.

It’s also worth noting that the inflation increase of the past two months occurs at a rate significantly higher than the oil price suggests, which might indicate a hint of ‘premature celebrations.’

We see a similar picture in Europe, with the caveat that the Eurozone lags a few quarters behind the US. This means base effects initially depress the headline inflation before it rises again.

If prices don’t increase at all in the coming months – a near impossibility due to the surge in oil prices – inflation will bottom out in October at 2.5%. This means that even in this scenario, inflation does not fall within one percentage point of the pre-Covid level.

If monthly inflation in the Eurozone equals 0.2% from here on – consistent with the long-term average – it will be April next year before inflation comes within that one percentage point. This would represent a total period of 3.25 years before the shock has been erased, longer than the average of the 100 inflation shocks studied by the IMF. And with a monthly oil-driven increase in September much bigger than 0.2%, it may take even longer.

Conclusion

If the Federal Reserve and the ECB consider the IMF study on 100 inflation shocks in 56 countries since 1971 in their decision-making, there is little reason to stop the series of interest rate hikes. This especially applies to the ECB, where inflation is nowhere near the pre-shock level and will probably take longer than average to reach it. For the Federal Reserve, the picture is slightly more nuanced, but the experience from the 70s suggests that complacency could be a significant risk.

Given that central banks aim for a soft landing, they will try to raise rates as little as possible and instead reiterate (endlessly) that rates will remain higher for longer. However, historically, we have reached a point where significant monetary tightening began to hurt the economy. The forced choice for stagflation, partly caused by rapidly rising oil prices, undoubtedly increases the risk of a recession. It seems a matter of time before markets realize this.