The US lost its AAA-Rating – Why it does matter (I)

The downgrade of the world's most important bond market emphasizes big questions about long-term debt sustainability, period!

Welcome from a finally sunny France. Below you will find a recent post Jeroen did on the US downgrade by Fitch. It’s a one of two, so expect the second part to arrive in your inbox soon.

Goodbye AAA

The United States is no longer part of the exclusive list of countries with a ‘triple-A’ or ‘AAA rating,’ the highest credit score awarded by the major rating agencies Fitch, Moody’s, and S&P Global.

The reason for this is that Fitch, on August 01, downgraded the US credit rating to AA+. Only nine ‘pure’ AAA-rated countries remain: Australia, Denmark, Germany, Luxembourg, the Netherlands, Norway, Singapore, Sweden, and Switzerland (chart source Bloomberg).

Make sense?

Fitch’s downgrade of the United States has caused quite a stir. US Treasury Secretary Yellen was quick to point out that the decision felt arbitrary and outdated. It’s worth noting that S&P Global had already downgraded its US credit rating back in 2011. Other ‘prominent’ figures, like Lawrence Summers, have also complained, emphasizing that America’s likelihood of defaulting on its debt is zero.

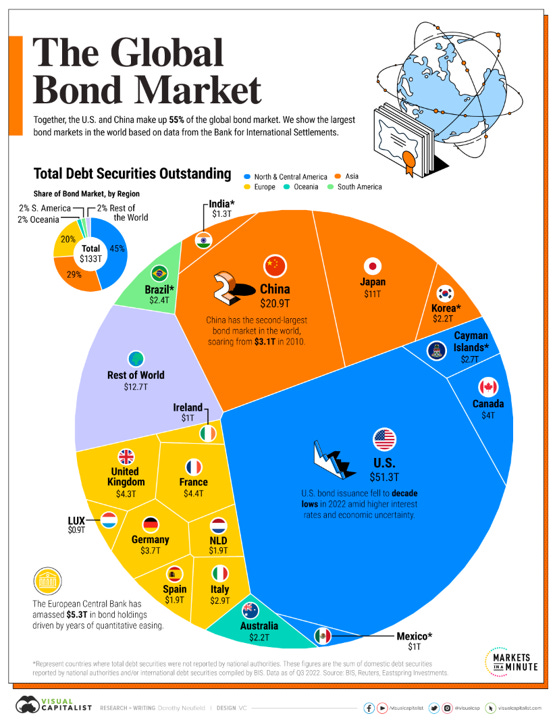

At least in the short term, Summers is right. Moreover, the US Treasury market is the world’s largest, most liquid, and safest bond market. When the world economy falters or financial markets panic, many investors seek refuge in US Treasury bonds.

An unsustainable trajectory

However, this does not mean that the US should be immune to the scrutiny of rating agencies. Regardless of its position as the most vital bond market in the world, the American debt and debt burdens are clearly on an ‘unsustainable trajectory.’

Let me clarify this with a few graphs. The US Congressional Budget Office (CBO), which provides independent budget and economic analyses for the US Congress, estimates that the debt-to-GDP ratio will rise in a straight line from about 100% now to 181% in 2053. For those who remember, the Eurozone had long worked with the Maastricht Treaty, which required countries to aim for a debt-to-GDP ratio of 60%. Hence, the US is heading towards three times (!) that target. And it’s not alone! For example, Italy, with a current debt ratio of 144%, is ‘well’ on its way to surpassing the 181% level by 2053.

Soaring interest costs

If you embrace the idea that there is an (implicit) limit to how high a country’s debt-to-GDP ratio can become, regardless of the fact that we are talking about the most important bond market globally, then Fitch has a point in downgrading the US credit rating.

Obviously, it’s no coincidence that Fitch’s downgrade comes when interest rates have just surged. The graph below shows that the US is estimated to spend 4.4% of GDP on interest costs next year. This is the highest level since 1996, leaving that 4.4% unavailable for other expenditures.

To further illustrate the impact of interest costs, here’s another graph from the CBO. It indicates that the primary budget deficit – simply the difference between expenditures and revenues – is expected to remain stable between now and 2053, at about 3%. This means that the US is consistently overspending by 3%. However, the graph also shows that the total budget deficit rises to more than 10%(!) of GDP over this period.

The difference between these two deficits are interest payments. Again, the US is by no means an outlier here. The trend in interest costs becoming an increasingly dominant factor in the total budget deficit due to the growing debt (as a percentage of GDP) is also observed in other countries. From this perspective, more rating downgrades should not be ruled out. Canada, which shares many similarities with the US and is characterized by an extreme housing market bubble, seems a likely candidate.

Looking ahead

What strikes me is that the debate surrounding the US rating downgrade currently unfolds on two fronts. The first focuses primarily on the ever-increasing interest costs that need to be paid. This is not surprising, given the recent surge in interest rates.

The second centers around the question of whether this downgrade will have a significant impact on financial markets or not. It is often argued that the attractiveness of the American Treasury market as a ‘safe haven’ remains largely unaffected and that major institutional investors such as pension funds and insurers are not forced to sell their holdings due to this downgrade. Additionally, the regulation regarding American Treasury bonds as collateral and their status within bank reserves is not up for debate. At least not now.

While I understand both discussions, to me, they do not address the elephant in the room. The downgrade of the US underscores (once again) the issue of debt sustainability. The real question that should be addressed is what it will take to ensure debt sustainability and how debt-to-GDP ratios can be lowered without collapsing the current financial system. In my next post, I will explore the far-reaching consequences of the choices that will have to be made to ‘solve’ the debt sustainability issue.

This is largely because some obvious solutions, such as realizing faster economic growth and implementing austerity measures, will likely fail. Hence, we must explore alternative solutions that will decisively impact the composition of a ‘sound’ investment portfolio and the outlook of traditional and alternative asset classes. I will extensively discuss this in Part II.