What do they actually mean by inflation?

Powell & Co. have stopped talking about inflation measures they once thought were key. How convenient!

Next week, the US inflation report for November is scheduled for release, and it will likely cause significant short-term volatility in markets. However, if you step back from the somewhat shortsighted market reaction to incoming consumer price data, one thing becomes clear: there is no such thing as ‘the’ inflation number. And the behavior of central banks is the most telling evidence of this.

3-month annualized what?

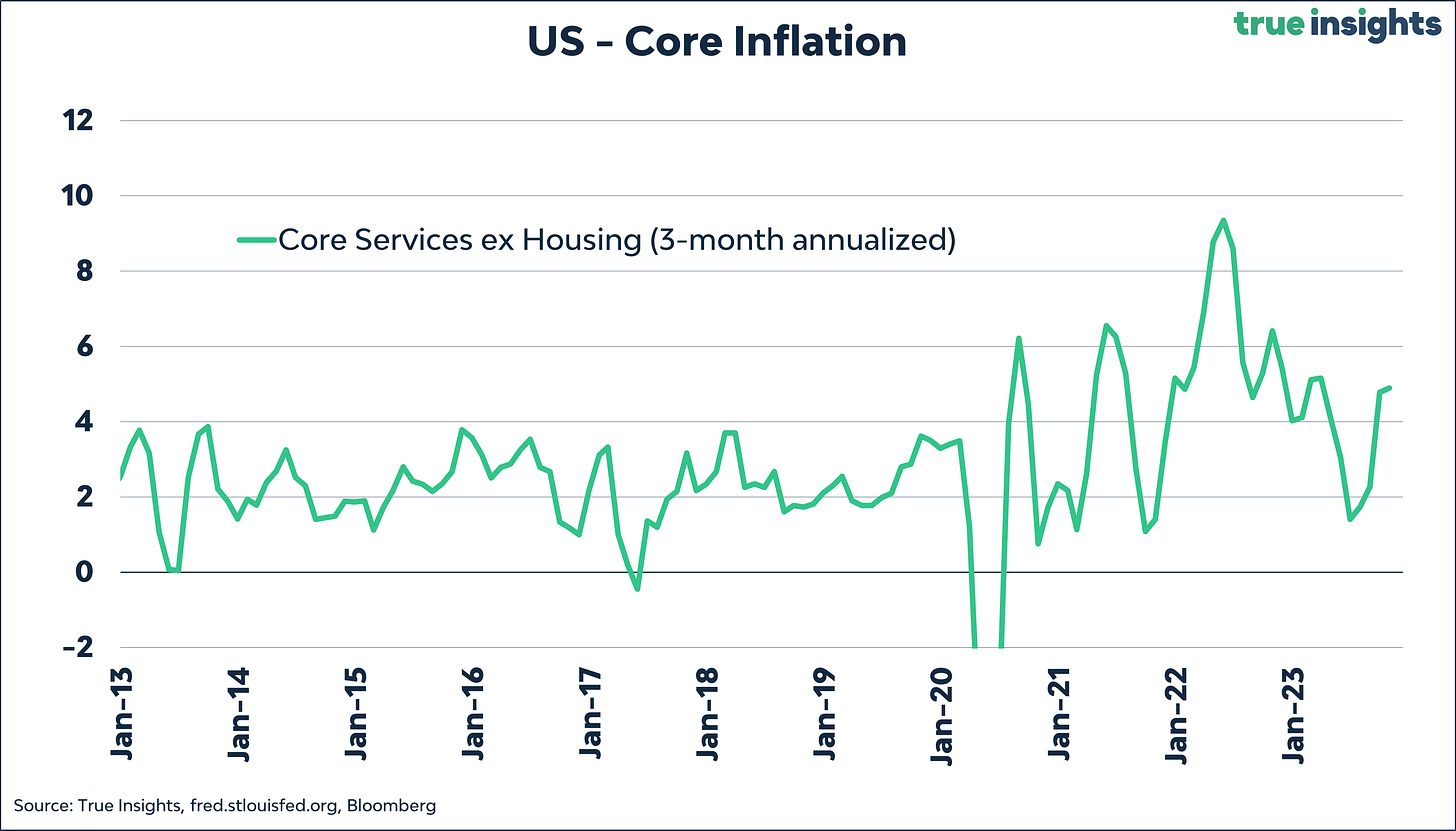

Not too long ago, the Fed Chairman forced us to focus on a very specific inflation figure, the 3-month annualized Core Services ex-Housing CPI. The idea was that a better picture of the’ real’ inflation trends could be obtained by looking at this relatively small, specific part of the inflation basket. After all, both headline and core inflation – the latter measure has always been the holy grail for ‘inflation experts’ – were terribly distorted by all the COVID and supply chain disruptions.

But just as the core and especially headline inflation have declined significantly, Powell and his colleagues talk little about the Core Services CPI. Perhaps it is ‘logical’ for the Fed to revert to the traditional inflation metrics as the economy normalizes. However, when I look at my US Inflation Monitor, which includes six different CPI measures, including Core Services ex-Housing, this little-communicated focus shift is quite ‘convenient’ for a central bank reluctant to raise interest rates again. The 3-month annualized Core Services ex-Housing CPI has risen for four consecutive months and reached 4.9% in October, significantly higher than both headline and core inflation.

Consumer expectations

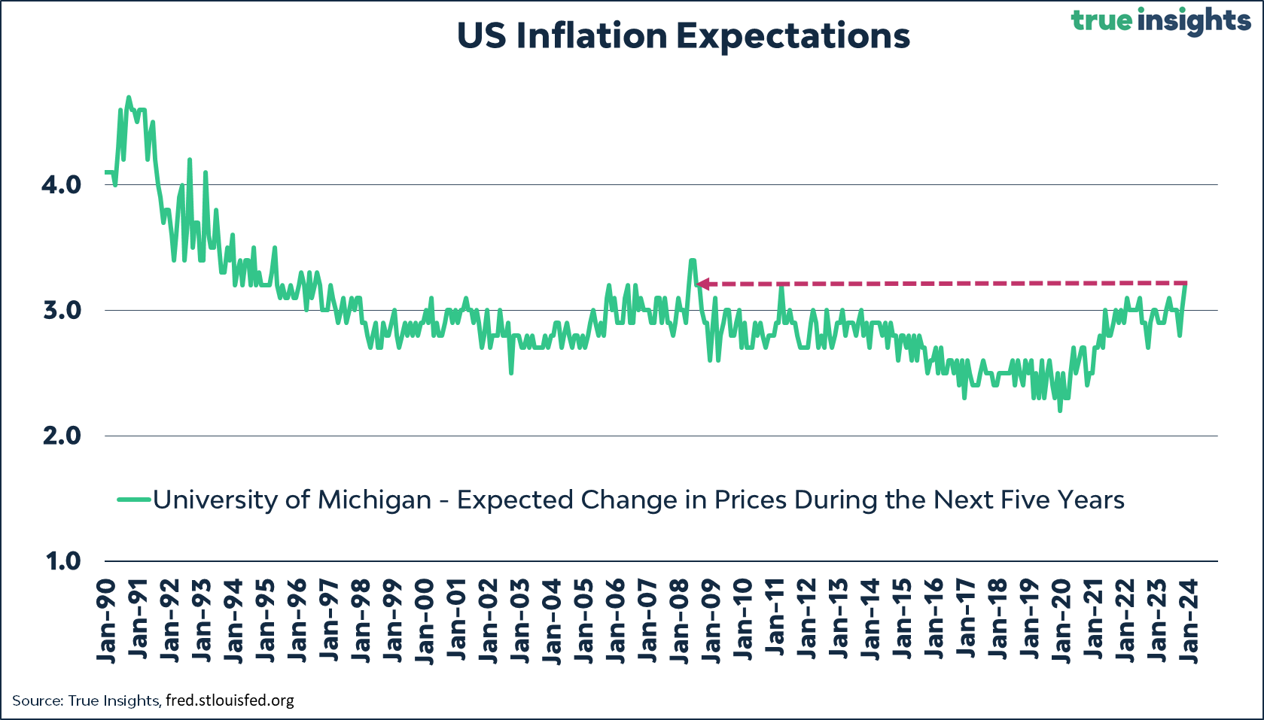

The Core Services ex-Housing CPI is not the only inflation metric that has faded into the background. There was that one press conference in 2022

during which Powell directly referred to consumer expectations, measured by the University of Michigan, as a justification for not raising rates by 0.50% but by 0.75%.

But if these expectations were, at the time, so important for maintaining price stability, what should we make of the fact that long-term expectations are now higher than during that press conference last year? In fact, in November, consumers expected the highest inflation in the next five years since 2008. Add to that the expectation for the next 12 months, which soared to 4.5% – nowhere near the Fed’s target – and you will wonder why the Fed and Powell are largely avoiding these figures.

Just human, after all

Central bankers are like us humans. While it would go too far to conclude that they are just making things up as fresh data comes in, the above does suggest that, at times, central bankers don’t exactly know what they should be doing and which inflation metrics they should be focusing on. This raises the question of whether a long-term inflation target of 2% will remain so sacred. But that’s for another time